Guest post by Isabella Whitworth (@Orchella49).

Roccella gracilis on wool yarn that has been dyed with orchil made from Lasallia pustulata. Image credit: Isabella Whitworth .

Lichens are complex plant-like organisms made up of a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium that live together in a mutually beneficial relationship (symbiosis). They are often found attached to rocks or trees and species can vary hugely in appearance, from flat, crusty forms to leaf-like growths. Certain species have been used as dyestuffs for millennia, although not all lichens produce dye.

My research into dye lichens was triggered by a chance mention of ‘an archive in the attic’ by local friends. Their forebears were dye manufacturers in nineteenth century Leeds in the UK and the company archive had been passed down three generations. The company’s initial fortunes came from the successful processing of orchil, a dye made from lichens.

As a textile artist and dyer, I was familiar with the practical use of natural dyes, but I had no knowledge of the historical trade in the lichens used to make some of these dyes. My studies of the archive revealed several aspects of the trade in the nineteenth century, which had followed centuries of orchil use in Europe.

Orchil was historically used to dye silk and wool various shades of purple, red and pink. It is frequently found as an ingredient in historical recipes to produce browns, pinks, lavender greys and purples and was known to impart a ‘fresh bloom’ to dyed colour. Many natural dyes require mordanting, a process that takes place before dyeing to enable the dye to form chemical bonds with the fibre. Substances such as alum, tannin and tin are used in a mordant bath. Orchil requires no mordant, which was especially advantageous in silk dyeing because mordants can make silk feel harsh to the touch.

A timeline of historical orchil lichen use reveals a voracious trade that continually expanded to new geographical areas. This was inevitable because the commercial collection of slow-growing lichens was ruthless and highly competitive. Areas were stripped out, allowing lichens no time to regrow and thus depleting natural populations. New sources were always vital, and with the colonial expansion of the nineteenth century, further territories became available to merchants and speculators who could amass huge fortunes through this one dyestuff.

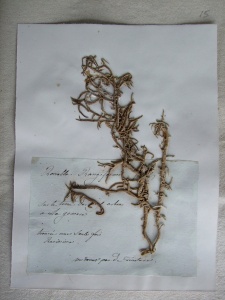

Page from 1830s collection of dye lichens made in the Canary Islands by J.M. Despréaux, found in the Leeds archive and now with the Economic Botany Collection, Kew.

Before the 1830s, various historical records report lichens collected from areas such as Scandinavia and Scotland (likely to have been Ochrolechia tartarea and Lasallia pustulata) and the islands of the Mediterranean and Atlantic (probably Roccella spp). The Canary Islands were a lucrative source of orchil until a serious collapse of lichen populations in the early 1800s. In the 1830s, political changes in South America enabled new trade in a lichen called Roccella gracilis from the countries now known as Ecuador and Peru. The Portuguese profited from a rich source of highly prized lichen from Angola (Roccella montagnei) and records from Leeds suggest that slaves were involved in transporting dyestuff from Angola’s interior to the coast.

Lichen is light when dry and can be compressed into a bale. A stockbook from the Leeds company archive listed the contents of the warehouse in 1877. My calculations suggest that the 55 tons of compressed lichen contained there would have equalled the volume of six modern double-decker buses. Lichen sources listed in the stockbook include Cape Verde, Angola, Mauritius, Mozambique, Zanzibar, Lima, Ecuador, and Galapagos as sources. One can only imagine the quantity of dyestuff stored throughout Europe during the nineteenth century, and the pressure exerted on populations of lichens.

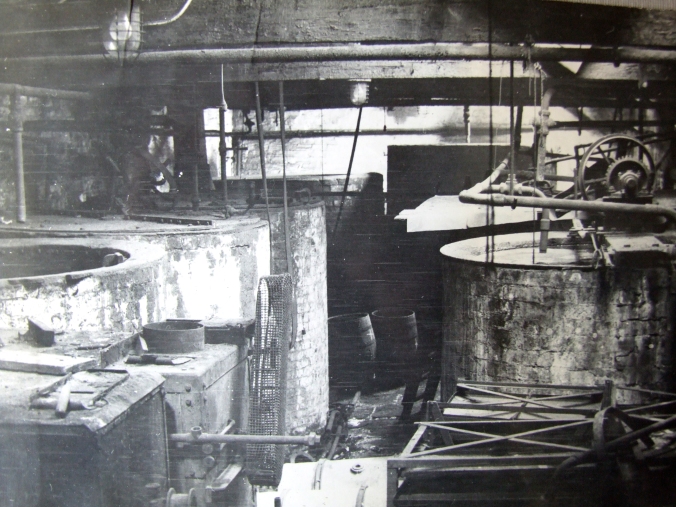

Manufacture of orchil is not straightforward. The dyestuff is not instantly available from the lichen and must be fermented in water and ammonia to break down the colourless compounds that are the dye ‘precursors’. Improvements in chemistry in the nineteenth century made the processing of orchil more efficient. Pure ammonia (as opposed to stale urine) gave clearer colours, and the inconsistent, lengthy fermentation period was speeded up in mechanised pans, which regulated temperature and the essential introduction of oxygen. Ordering and despatch times were reduced because advances in technology made it quicker and easier for buyers, agents or merchants to communicate. These factors placed additional pressures on lichen populations.

Mechanised orchil pans known as ‘magogs’. The design was patented at the end of the nineteenth century and used until the 1930s in Leeds.

By the mid-nineteenth century, orchil lichens were gathered commercially all over the world. But this massive trade wasn’t to last. In 1856, a chemist called William Henry Perkin discovered a purple substance derived from coal tar when he was trying to synthesise quinine. He realised its potential as a dye and named it ‘mauveine’. His discovery led to the birth of the synthetic dye industry. Although it took many years for orchil use to decline significantly, the new synthetic dyes slowed the ever-widening search for new sources of lichens.

About the author: Isabella Whitworth trained as a graphic designer, working as an editor, manager and designer in industry. A mid-life career change saw her exhibiting as a textile artist and developing a passion for the study of natural dyes. Follow her on twitter (@Orchella49).

That was an absolutely fascinating read!

The is an absolutely fantastic post. Amazing subject. Thanks so much for sharing!

One wonders whether these lichens have naturally restored themselves. I would expect so, although I would expect the hundred years of pollution might have stalled them in the UK before the clean air acts.

This is difficult to answer. I’m neither a botanist nor mycologist so I’ll just tell you what I know of the trade. Lichens in commercial use were known as ‘weed’ (the foliose kind growing on rocks or trees) and ‘moss’ (the crusty or biscuit-like growths). There are some botanical names appearing in records but they cannot be relied upon: they may have been accurate for the knowledge of the time, or maybe not. Many lichens look extremely similar, botanical naming of lichens was still in its infancy in the 1800s, and the Leeds archive demonstrates the time spent by the Leeds dye manufacturer in trying to identify lichens for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Basically, I’m saying it’s not possible to be sure what lichens were being collected, and thus not possible to know what has disappeared – or been restored.

The current absence of dye lichen in a collecting site doesn’t necessarily mean it was wiped out by over-harvesting either. There are so many factors involved, such as pollution, changes in climate, building development, agriculture etc. I hope that answers a little of your question.

Thank you for a very interesting post! I know that Ochrolechia tartare was an export article from Norway. But I also have read that the color of the dye made from this lichen was fading quite fast when exposed to light. Do you know if this was the for the other dyes as well?

All orchil dye, no matter which lichen it is made from, is very light fugitive. This fact was well known to dyers and the advantages of the colour were clearly recognised, but orchil appears in countless historical dye recipes despite its shortcomings. As a dyer, I know how beautiful the colour can be and its historical use does not surprise me. I have had the privilege of seeing this colour at its best when freshly dyed.

However, don’t confuse orchil with other lichen dyes that come from lichens such as Parmelia saxitilis or P. omphalodes. Orchil must always go through a process of fermentation to ‘release’ the dye precursors and this can take several weeks. Only then can it be used to dye silk or wool. Other lichens will produce rusty reds, browns, gold etc and can be put straight into the dye pot with the fibre, thread or cloth. The ‘crotal’ dyes of the Highlands are examples of this, often found in Harris Tweeds where the lingering and (to me) pleasant earthy smell of the lichen-dyed wool is believed to deter moth attacks!

I should have added to the reply above that the non-orchil lichen dyes are known for much better lightfastness.

Pingback: Guest blog for Plant Scientist | Isabella Whitworth

Pingback: An unsustainable trade | Spinning, Weaving and ...

Hello and colorful greetings from the Canary Islands!

Our orchil family was about to disappear because of overexplotation and is a highly protected species. There is still a lot of geographic names that refer to places where orchil was harvested, mainly steep cliffs where the lichen finds ideal conditions.

hi, what would be your take on the harvesting of lichen now to produce vitamin d3 it seems to be catching on in hundreds of products, yet i cant find a manufacturer of heard of any one harvesting enough to supply the world demand, surly its unsustainable.

the companies selling this claim its sustainably sourced, they would.

Hi Mike, I don’t know much about this, but Lichens grow rather slowly so I would think it would be quite hard to produce them sustainably.