By David Parrish

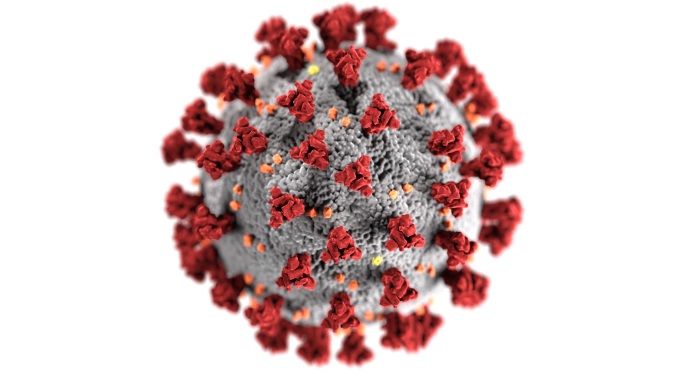

Illustration of the structure of a coronavirus particle. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Public domain.

The “novel coronavirus” has many of us cringing at every sniffle, cough, and sneeze we hear (or utter). Anxiety levels are high and justifiably so. Perhaps shedding some light on viruses can help us deal less anxiously with this new one. The old Irish proverb comes to mind: “better the devil you know.”

Viruses inhabit an interesting space in the field of biology. Only a few thousand have been named (versus more than a million species of plants, animals, and fungi), but viruses are likely the most abundant form that biologists study. Here’s the logic. Humans are subject to infection by many different viruses, most of which infect only us, and the same appears to be true for every species of animal, plant, fungus, and bacterium. Accordingly, we can reason that viruses are the most abundant things biologists study.

However, most biologists do not consider viruses to be truly alive. Since the 19th century, biologists have agreed that living things are made of cells – the complex building blocks of life. Viruses are not cellular. They are quite simple, made of DNA or RNA, a few proteins, and (sometimes) oily substances. They do not carry out the biochemistry associated with life. Antibiotics (the name means “against life” or “not fit for life”) are not effective against viruses exactly because viruses do nothing that an antibiotic can attack.

But viruses do some things that make them seem to be alive. They act a lot like bacteria and fungi in their ability to invade organisms, cause diseases, reproduce, disperse, and then repeat the cycle. It is an act, though, not really life. Living microbes that cause diseases (bacteria and fungi) generally grow and make more of themselves in cavities or on cell surfaces of their “hosts” (victims). They live outside of the hosts’ cells and cause diseases by multiplying, producing toxins, or other effects. By contrast, viruses enter a host cell, unpack their DNA or RNA, commandeer the cell’s metabolic machinery, and cause new virus parts to be made. The parts self-assemble and the resulting viruses can disperse and repeat the process. In essence, a virus is a non-living, stripped-down, nano-robot-like, biochemical assembly that invades cells and hijacks them to make more viruses.

In animals, if a virus invades cells lining air passages, the symptoms will be respiratory – from colds to bronchitis to pneumonia. Several different human viruses attack liver cells and can cause hepatitis. Some viruses can turn genetic switches in infected organs and cause cells to divide malignantly. The human papillomavirus (HPV) is a well-studied virus known to cause cancer, and HPV vaccines have been shown to be quite effective in preventing both HPV infections and associated cancers.

Where does a novel coronavirus – or any new virus – come from? How does a fatal disease like Covid-19 suddenly appear? Unfortunately, a never-before-seen virus with lethal potential can be produced in just one viral generation. The genes (DNA or RNA) that viruses carry are subject to mutation and new combinations. Pieces of DNA from host cells can be picked up by the virus, potentially making it more easily spread, more lethal, or both. In this way, viruses evolve to produce new forms just as living things do.

In another cruel twist, a host cell may be invaded simultaneously by two different viruses and forced to make parts for both. As those parts are self-assembling, mixtures of the two viruses may form. And those hybrids may have unique disease properties. Many virologists suspect that the virus causing Covid-19 resulted from this kind of mashup between something as innocuous as a common cold coronavirus and a coronavirus from a bat. Such cross-species viral hybrids seem inevitable in a world with ever increasing numbers of people and our continual encroachment on other animals’ territory. Both science and common sense are needed in this area.

Virologists, epidemiologists, and physicians still have much to learn about Covid-19 and the virus that causes it, but I am cautiously optimistic that the science being brought to bear on this new scourge will get us past it. And the hope is the knowledge gained will make us better prepared for scourges yet to come.

About the author: After earning his PhD in plant science from Cornell, Parrish joined the faculty of Virginia Tech’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, where he taught crop ecology and environmental science. His research interests spanned seed physiology, sustainable cropping systems, and biological sources for renewable energy. In his book, “The Gyroscope of Life” (Pocahontas Press, June 2020), Parrish brings biological studies to the curious non-scientist in an accessible and relevant way, inspiring readers to consider the world around us in a new light.

About the author: After earning his PhD in plant science from Cornell, Parrish joined the faculty of Virginia Tech’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, where he taught crop ecology and environmental science. His research interests spanned seed physiology, sustainable cropping systems, and biological sources for renewable energy. In his book, “The Gyroscope of Life” (Pocahontas Press, June 2020), Parrish brings biological studies to the curious non-scientist in an accessible and relevant way, inspiring readers to consider the world around us in a new light.

The first things I think of when I hear the word “algae” are the microscopic green cells that were the ancestors of land plants. Reading Bloom by Ruth Kassinger was a powerful reminder that algae are so much more than this. The term “algae” actually describes a diverse collection of lifeforms ranging from single-celled diatoms to kelp and other seaweeds*. In the book, the author explores the origins of algae, their modern uses in food and other products, and the emerging algae-based technologies that may help us save the planet in future.

The first things I think of when I hear the word “algae” are the microscopic green cells that were the ancestors of land plants. Reading Bloom by Ruth Kassinger was a powerful reminder that algae are so much more than this. The term “algae” actually describes a diverse collection of lifeforms ranging from single-celled diatoms to kelp and other seaweeds*. In the book, the author explores the origins of algae, their modern uses in food and other products, and the emerging algae-based technologies that may help us save the planet in future.

I spend my working life helping to repackage scientific findings into formats that allow them to reach new audiences, namely plain-language summaries and podcasts. So, when I was introduced to a SciFi novella for children that prominently features quantum physics, I was intrigued.

I spend my working life helping to repackage scientific findings into formats that allow them to reach new audiences, namely plain-language summaries and podcasts. So, when I was introduced to a SciFi novella for children that prominently features quantum physics, I was intrigued.